Newsletter Subscribe

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

In the fast-evolving landscape of artificial intelligence, few voices carry as much weight as Yann LeCun’s. As a Turing Award winner and former Chief AI Scientist at Meta, LeCun has spent decades shaping the field, from pioneering convolutional neural networks to challenging the status quo of today’s dominant AI paradigms. His recent departure from Meta to launch AMI Labs—a Paris-based startup valued at $3.5 billion—signals a bold pivot toward what he sees as the true path to advanced intelligence. In a series of high-profile interviews and lectures, LeCun has stirred controversy by arguing that current AI systems, despite their impressive feats, aren’t even as smart as a house cat. This isn’t hyperbole; it’s a calculated critique rooted in fundamental differences in how AI processes the world versus how living beings do.

Drawing from LeCun’s insights and broader discussions in the AI community, this article explores why he believes scaling up large language models (LLMs) is a dead end, what his alternative “world models” approach entails, and the implications for the race to artificial general intelligence (AGI). If you’re an AI researcher, developer, or simply curious about where the technology is headed, we’ll break it down with practical takeaways to help you decide which side of the debate to bet on.

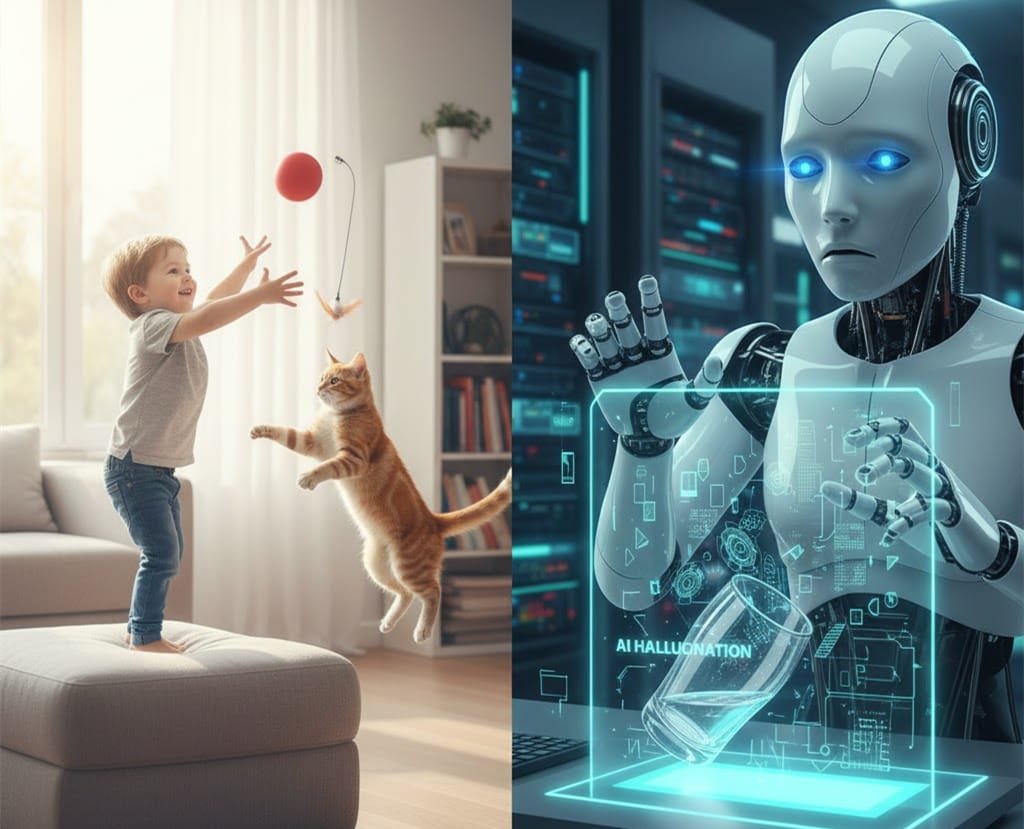

Picture this: Your average house cat navigates cluttered rooms with effortless grace, predicts the trajectory of a falling toy, and adapts to new environments without missing a beat. Now compare that to state-of-the-art AI like GPT-4, which can ace bar exams or generate code but hallucinates facts, struggles with basic physical reasoning, and lacks any real understanding of cause and effect. LeCun hammers this point home repeatedly: “Where is a robot that’s as good as a cat in the physical world? We don’t think the tasks that a cat can accomplish are smart, but in fact, they are.”

The core issue? Modern AI, built on autoregressive LLMs, excels at pattern matching—predicting the next word in a sentence or the next pixel in an image—but it doesn’t build an internal model of reality. Cats (and humans) don’t just memorize; they construct intuitive physics engines in their minds, allowing them to anticipate outcomes without exhaustive computation. LeCun argues that without this foundational “common sense,” AI will remain brittle, prone to errors in novel situations, and far from the flexible intelligence we associate with even simple animals.

This perspective isn’t new for LeCun, but it’s gaining traction amid growing skepticism about LLM hype. In forums like Reddit and X (formerly Twitter), developers echo his views, noting that while AI can “regurgitate” knowledge, it lacks the hierarchical planning and world simulation that animals take for granted.

One of LeCun’s most compelling arguments comes down to raw data consumption. He calculates that a four-year-old child, awake for about 16,000 hours, processes roughly two terabytes of sensory data per second through their neural pathways—totaling around 10^14 bytes by age four. That’s on par with the textual data used to train today’s leading LLMs. Yet, the outcomes couldn’t be more different.

A child emerges with an innate grasp of physics: balancing on two feet, catching a ball, or understanding object permanence. A cat, with even less data, masters stealthy leaps and prey prediction. AI, fed the sum of human-written knowledge, might translate languages or solve puzzles but can’t reliably simulate a glass tipping over without generating hallucinations. LeCun’s math underscores a inefficiency in current architectures—they burn through data without extracting the abstract, predictive insights that biological systems prioritize.

To illustrate the disparity, consider this comparison:

| Aspect | Modern LLMs (e.g., GPT-4) | Cats/Young Children |

|---|---|---|

| Data Processed | ~10^14 bytes (text-heavy) | ~10^14 bytes (sensory-rich) |

| Key Skills Unlocked | Language generation, coding, trivia recall | Physical intuition, balance, trajectory prediction |

| Reasoning Style | Statistical prediction of tokens/pixels | Internal world simulation for planning |

| Limitations | Hallucinations, no true understanding | Can’t code or pass exams, but adapts intuitively |

| Energy Efficiency | Massive compute (e.g., data centers) | Runs on kibble or milk (low power) |

This table highlights why LeCun calls LLMs a “dead end”—they’re data-hungry giants that mimic surface-level patterns without grasping underlying mechanics.

Enter LeCun’s antidote: Joint Embedding Predictive Architecture (JEPA), a framework he’s championed for years and is now advancing at AMI Labs. Unlike LLMs, which obsess over rendering every detail (like simulating each raindrop on a windshield), JEPA focuses on abstract representations. It predicts high-level states and consequences, much like a mental physics engine.

Imagine driving in the rain: An LLM-style AI might try to model every droplet’s refraction, leading to computational overload and errors. A JEPA-based system ignores the minutiae, instead noting “road is wet” and inferring “braking could cause skidding.” This shift from depiction to comprehension allows for efficient reasoning, planning, and even hierarchical decision-making—essential for real-world tasks like robotics or autonomous vehicles.

LeCun’s vision incorporates self-supervised learning from video and sensory inputs, enabling AI to build “world models” that simulate environments without generating them pixel-by-pixel. Early experiments, like Meta’s V-JEPA for video prediction, show promise in reducing hallucinations and improving generalization. If scaled, this could unlock AI that’s not just smart on paper but capable in the physical realm.

Not everyone’s convinced. Proponents of “scaling laws”—the idea that bigger models with more data and compute will magically yield AGI—counter that we’re building airplanes, not flapping birds. They point to physics as a statistical phenomenon: With enough thrust (compute), flight happens regardless of biology. Surveys show 76% of AI researchers doubt scaling alone suffices, but companies like OpenAI bet billions on it anyway.

LeCun retorts that without sensory grounding and world models, AI will forever “read the manual” without understanding the machine. Scaling might yield superhuman pattern recognition, but not the adaptive, goal-driven intelligence of a cat dodging traffic. The debate boils down to statistics versus simulation: Do we double down on data or emulate evolution’s efficiency?

If you’re deciding where to focus efforts—or investments—LeCun’s camp offers a pragmatic edge for embodied AI applications like robotics and self-driving tech. Scaling laws dominate short-term wins in language tasks, but hit diminishing returns as models grow unwieldy. A hybrid might emerge, but LeCun’s push for open-source JEPA-like systems could democratize progress, avoiding proprietary bottlenecks.

Ultimately, if history favors efficiency (think brains over supercomputers), world models win. Bet on scaling for quick ROI; back LeCun for transformative leaps.

LeCun’s critique isn’t defeatist—it’s a roadmap. By prioritizing world models over word models, AI could evolve from clever parrots to intuitive thinkers. As he puts it, true intelligence is about learning, not just predicting. Whether you’re coding the next model or pondering AGI’s future, this shift could redefine what’s possible. Keep an eye on AMI Labs; the cat’s out of the bag, and it’s leading the way.